|

|

|

|

|

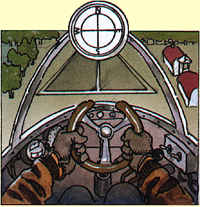

| Our desired course is due north. The plane has veered to the west. We correct by turning toward the east. |

Oops

- we've overcorrected. We need to steer to the west again. |

Arriving at the desired destination is a matter of many such corrections. |

To an observer on the ground, an airplane appears to fly in a beeline toward its destination. But things look very different from inside the cockpit. Buffeted by winds or shifts in air pressure, the plane regularly drifts off course. When this happens, the pilot makes a correction by steering the plane in the opposite direction. If the pilot overcorrects, then he or she must correct the correction, and so on. The plane actually flies in a zigzag.

|

Feedback is a central feature of life: All organisms share this ability to sense how they're doing and to make changes in "mid-flight" when necessary. The process of feedback governs how we grow, respond to stress and challenge, and regulate factors such as body temperature, blood pressure, and cholesterol level. This apparent puposefulness, largely unconscious, operates at every level - from the interaction of proteins to the interaction of organisms in complex ecologies. |

|

|